In November 2005, right when the first copies of the IPCC Special Report on Carbon dioxide Capture and Storage (SRCCS) were printed, climate negotiators gathered at COP11 in Montreal were suddenly confronted with the need to have a view not only on whether CCS should be allowed in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), but also by what rules. The CDM had been operational for a few years, had led to several large industrial non-CO2 greenhouse gas reduction and a lot of renewable energy projects, and a Japanese project developer considered this the right time for CCS to be included in the portfolio of CDM technologies.

It turned out to be much too early. The reasons why the negotiations on CCS in the CDM dragged on for years, and are at this point still not fully resolved, have been analysed and discussed in many publications and events. Indeed, there were many reasons. For example, given a limited demand for CDM credits, CCS might push renewable energy and energy efficiency projects out of the portfolio. In addition, many questioned the contribution of CCS, a fossil-fuel technology, to sustainable development, a prerequisite of the CDM. Lastly, the capacity of the developing host countries of CDM projects to regulate CCS adequately was doubted and the CDM does not foresee in rules to deal with the possibility of long-term impermanence of CO

2 storage.

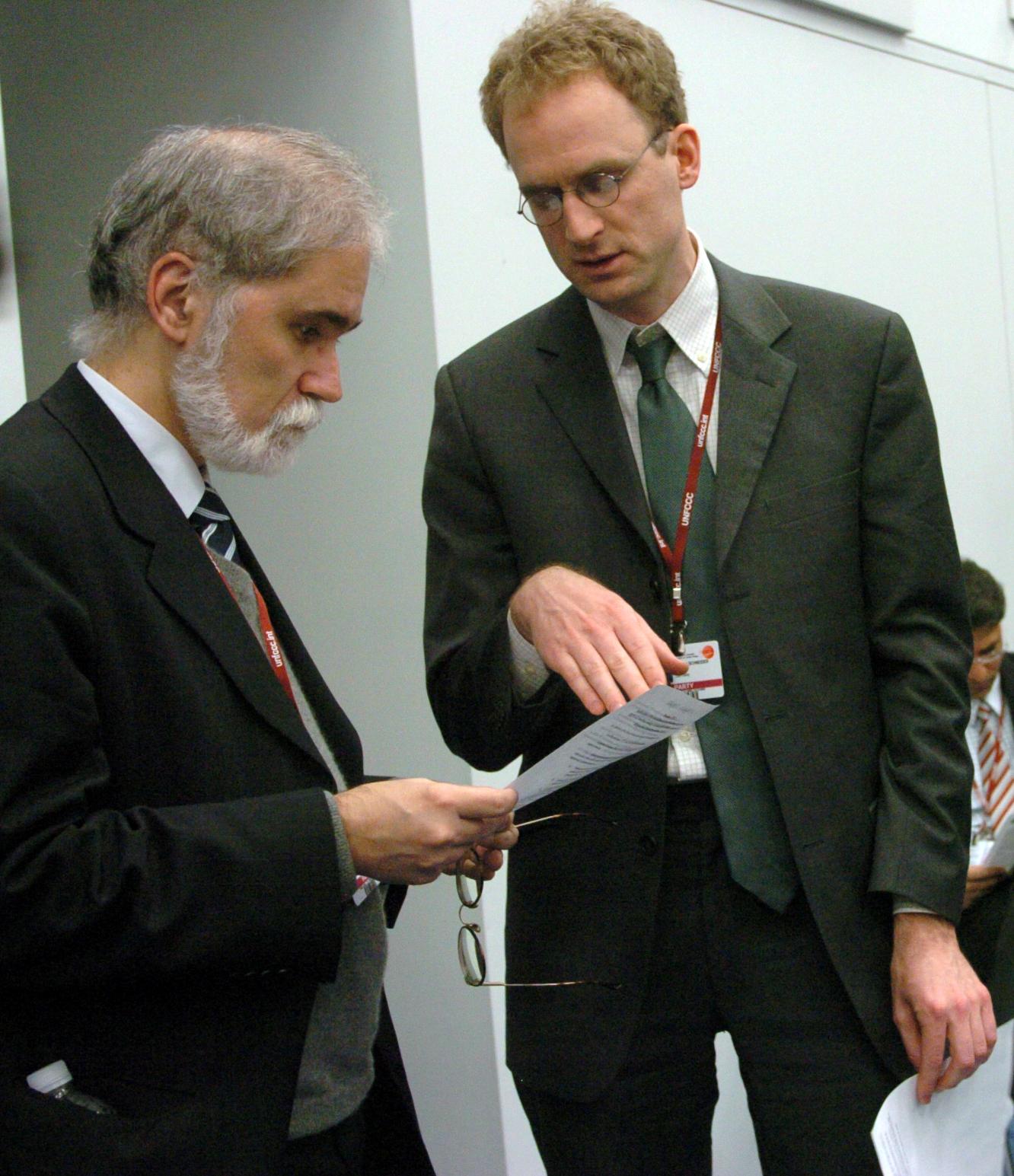

Two negotiators on CCS in the CDM, from Brazil and the European Union, discussing the text during COP11.

I would like to offer another explanation for the long-time controversy of CCS in the CDM: sufficient science-policy interaction was assumed by the initiators of the early CCS project submissions to the CDM. In reality, the negotiators had not completed the absorption of information from the SRCCS, let alone were they ready to approve a fossil technology into the already controversial CDM. They were pushed to a decision – and said no as they were not sure what they were approving.

The case of CCS in the CDM points at a broader problem: the information flows between science and policy. Scientists always keep an eye at what other researchers are doing, through the peer-reviewed literature and highly institutionalised conferences. They tend to forget that policymakers have no such tools. Their information reaches them through a number of informal channels, such as random meetings and lobbyists. They often don’t interact with scientists but with consultants, who summarise and interpret the latest science but are rarely in direct contact with those doing the research, and generally don’t read peer-reviewed journals – the preferred means of dissemination for academics. For policymakers in developing countries, the situation is often much worse.

Many research projects, including those financed by the European Commission such as the CO2ReMoVe project that this blog is reporting on, are required to disseminate their research results. This is a very good aim. The trouble is, however, that researchers are often not aware of the information needs of policymakers and lack the skills to communicate effectively and at the right level of detail with policymakers.

The CO2ReMoVe project is no exception; it remains a challenge to align the research results in such a way with the policy process that they can have direct relevance. Sometimes we were lucky: Three CO2ReMoVe researchers presented results in the technical workshop on CCS in the CDM in Abu Dhabi, directly contributing to a policy process that happened to gain momentum when the research results came out. On other occasions, such as with the European Commission Directive on geological storage of CO2 and its transposition to Member State legislation, the link between the CO2ReMoVe results and the policy process could not be laid.

To be policy-relevant, intermediaries are needed and researchers have to develop new skills – give accessible presentations at policy forums, answer questions from policymakers, and ... write blogs.

Heleen de Coninck

Programme manager ECN Policy Studies

Heleen de Coninck works as a programme manager in International Energy and Climate Issues at ECN Policy Studies. Her main research focus is international climate policy and technology, in particular CCS. Heleen was an editor of the IPCC Special Report on CO2 capture and storage, worked for the European Commission on the Directive on geological storage, for several UN organisations on CCS and the CDM and in new climate policy mechanisms and has published widely on CCS policy issues. In CO2ReMoVe, Heleen works on policy integration of the project results.